Carl Wittwer, MD, PhD, and Noriko Kusukawa, PhD, who is Wittwer’s wife, are retiring from ARUP Laboratories to move to Maine, where they are building a home with a fully equipped molecular laboratory.

To say Carl Wittwer, MD, PhD, is retiring isn’t exactly accurate.

Ask the pioneering scientist, widely recognized for having revolutionized molecular diagnostics, what he’ll do when he “retires” from ARUP Laboratories on July 1, 2020, and he’ll say he will do the same thing he has done nearly every day since he was a teenager tinkering with old TV sets in his parents’ Michigan basement: He’ll go to his laboratory and fashion an idea into one prototype after another until he gets what he wants.

“I’m going to do what I like to do, and what I might be good at doing,” Wittwer said in what arguably may be the understatement of the past few decades.

Wittwer, medical director of Immunologic Flow Cytometry at ARUP, is moving to Maine, where he and his wife, Noriko Kusukawa, PhD, ARUP vice president of innovation and strategic investment, are building a home in a coastal village that will include a fully equipped molecular laboratory. Kusukawa is also “retiring.”

Wittwer is looking forward to doing more research and experimentation on his own. “If I have any talent, it’s mainly in doing the work myself. I’ve learned to direct people at least adequately, but you lose something doing that,” he said.

Wittwer came to ARUP and the University of Utah in 1988 as a pathology resident, but before his arrival, he had already begun experimenting with ways to perform tests more quickly. While pursuing a PhD in biochemistry at Utah State University, he was doing research that involved measuring a particular enzyme in vitamin metabolism using an assay that took a whole day to run. He ended up devoting a year of his PhD program to developing a test that took just 10 minutes to perform.

“People thought that was sort of ridiculous because I spent a year to save 11 hours or something like that,” Wittwer said. “But to be able to achieve something and to learn from it on a rapid turnaround always seemed preferable to me.”

His belief in the importance of speed would lead to countless breakthroughs in molecular diagnostics and come to define a brilliant career. Wittwer holds dozens of U.S. patents and their foreign equivalents and has published more than 200 articles and book chapters on molecular diagnostics—so far.

He also has won countless awards, including the 2015 Utah Genius Lifetime Achievement Award, the 2015 Pioneers of Progress Award in Science and Technology Development, the U of U 2017 Excellence in Innovation and Commercialization Award, and the 2019 Cotlove Award from the Academy of Clinical Laboratory Physicians and Scientists.

“He is an incredible innovator and inventor,” said Peter Jensen, MD, chairman of the U of U Department of Pathology and chairman of ARUP’s Board of Directors. “He has had a major international impact.”

After completing his PhD, Wittwer went to medical school at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. It wasn’t long after returning to Utah as a pathology resident that he established ARUP’s first molecular diagnostics lab.

Now a mainstay of laboratory medicine, molecular diagnostics at the time was considered a risky venture for ARUP or any other reference lab. Many viewed it as an exclusively academic pursuit because assays took too long to perform and required a significant commitment of labor and equipment. Molecular diagnostics was a guaranteed way to lose money, Wittwer said.

But Carl Kjeldsberg, MD, ARUP’s CEO at the time, took a leap of faith and approved the purchase of an oligonucleotide synthesizer needed to create the lab. “I remember Carl telling me that he was raked over the coals for the extravagant expenditures and somewhat crazy direction of molecular diagnostics,” Wittwer said. “But in retrospect, it turned out to be the right thing to do.”

In the lab, with a part-time technologist to assist him, he began to experiment with polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which was still a relatively new methodology for amplifying a small sample of DNA into an amount large enough to study in detail. Wittwer sought to create an instrument that could speed up PCR, which relies on repeated cycles of heating and coolingto cause reactions that depend on temperature, specifically DNA melting, primer annealing, and DNA replication. PCR is integral to the diagnosis of infectious diseases as well as the diagnosis of genetic disorders, among many other applications.

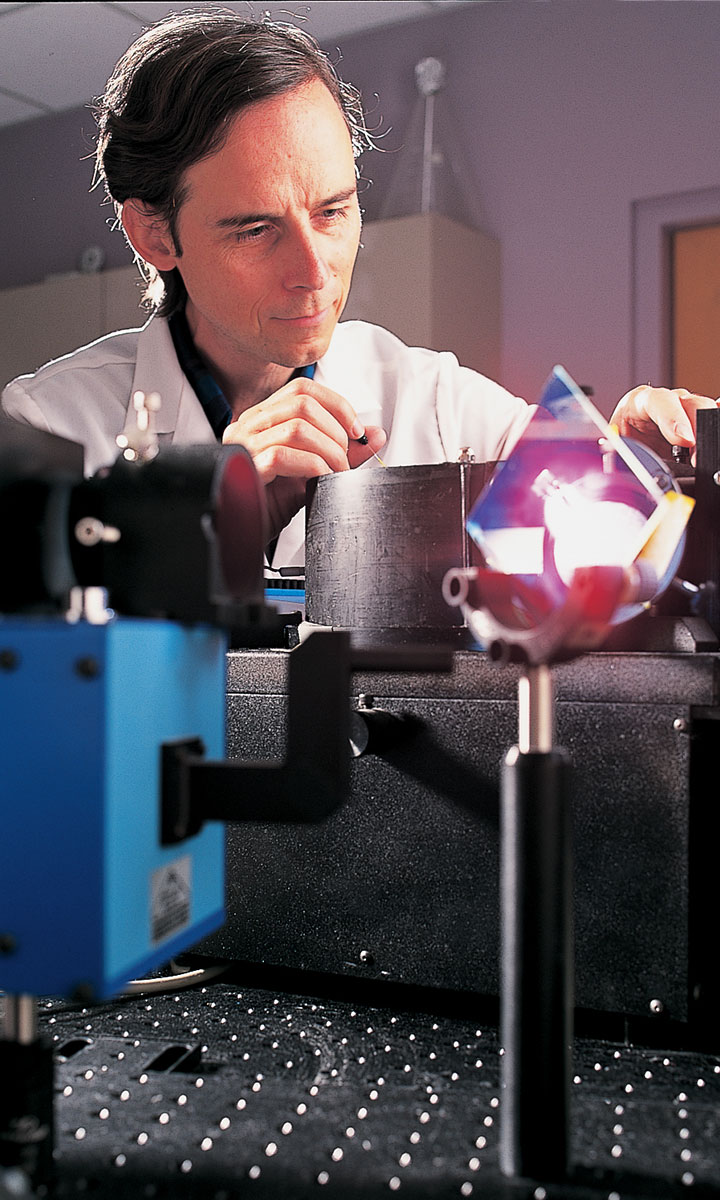

Carl Wittwer, MD, PhD, with the LightCycler instrument he invented.

Initial prototypes, famously fashioned from hair dryers and vacuum cleaners, evolved into the RapidCycler, an instrument capable of performing PCR in 10-15 minutes rather than up to four hours. From the RapidCycler emerged the more sophisticated LightCycler as Wittwer continued to improve upon his invention, which he and his partners commercialized when they formed Idaho Technology in 1990. In the late 1990s, Roche licensed the instrument and distributed it worldwide.

Now called BioFire Diagnostics, Wittwer’s company was acquired by the French company bioMerieux in 2014 for $450 million.

Wittwer’s inventions did not end there. In his lab, he has focused on simplifying DNA analysis by removing the need for preprocessing steps. He also has worked to develop instruments for performing simple, homogenous DNA techniques on a chip for genetic analysis.

He is far from finished. In the new lab he is building in Maine, “I’ll continue to try to push the speed of amplification, looking at different polymerases and different methods,” he said. “I’ll be going back to pieces and parts and will be trying to put things together.”

Wittwer is clear about the basic problem he has spent his career trying to solve.

“Humans and their instruments are slow, but biochemical reactions are very fast, so it’s our own limitations, not the inherent limitations of biochemistry, that slow us down,” he said. “It’s our job to build faster instruments, to build things that become more useful and give us more information.”

This is particularly true when these instruments produce information vital to treating patients, Wittwer said, in part explaining why the only full-time job he has held for the past three decades has been at ARUP. “The opportunity at ARUP to make a difference in people’s health was always a strong draw.”

At ARUP and the U of U, Wittwer said, he has found superiors and colleagues who understand that “the best way to handle and encourage me was to mostly let me run free. It’s been a great place to work.”

“But when you do something for 32 years and you like to believe that you’re capable of continued thought and contribution, you don’t want to get repetitive and be limited by routine,” he said. “It’s been phenomenal, but maybe there’s something out on the East Coast in the woods of Maine that I should be exposed to.”

Scientists with whom Wittwer has worked at ARUP and the U of U describe his departure as a watershed moment for the company and the university.

“I am in awe of everything he has brought to the table. It’s really unparalleled,” said ARUP CEO Sherrie Perkins, MD, PhD. “Carl’s ability to see and grasp new technology has made ARUP so much stronger. I’m really very sad to see him go. He has been such a vital part of ARUP.”

For his part, Wittwer also is sad to be leaving ARUP, despite looking forward to his move to Maine. He is especially fond of Maine because it was there he met Kusukawa in 1993, when, as an executive for an agarose supplier, she invited him to do a scientific presentation at her company.

Kusukawa will leave her own indelible mark on ARUP. An expert in fostering innovation in academia and in commercializing academic discoveries, she is responsible for numerous strategic partnerships that she initiated and has nurtured to the great benefit of ARUP over her 20 years of service.

“We’re both very grateful to ARUP and to the Department of Pathology. They deserve our thanks and respect for putting up with our strange activities,” Wittwer said. “We are not typical or conventional as a pair, and we thank everyone for their help and interaction.”