Sick of Being Sick Six Families Help with Discovering Disorder

Discovery of a New Immune Disorder Leads to Answers and Earlier Treatment

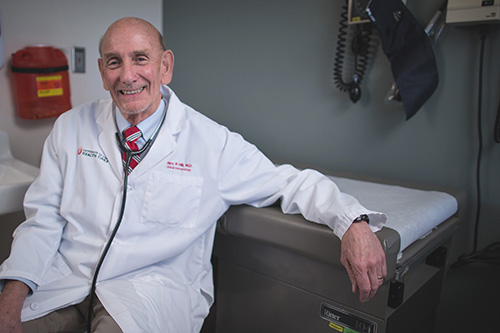

Credit: Deseret News, Jeffrey D. Allred

Pneumonia has been an uninvited visitor throughout Roma Jean Ockler’s life, showing up every few years. Two years ago she almost died from a case so severe that it landed her in surgery. Sinus infections intruded even more frequently, hacking into her life every six weeks or so.

“Dealing with being sick becomes part of your life; you don’t ever seem able to stay away from the doctor’s offi ce,” says Ockler, a mother and grandmother, whose original diagnosis in 1975 was a weak immune system. “It got incredibly frustrating.”

Harry Hill, MD, often sees this frustration in patients who visit the Clinical Immunology/Immunodefi ciencies Clinic at the University Medical Center. By the time they arrive at his clinic, these patients have had one infection after another, often enduring a maddening diagnostic odyssey lasting years. Hill is medical director of the Cellular and Innate Immunology Laboratory at ARUP.

Many of these patients end up being diagnosed with common variable immune defi ciency (CVID), a rare condition in which patients have dangerously low levels of infection-fi ghting antibodies. Hill estimates he’s diagnosed between 200 to 300 patients with CVID, a condition occurring in about 1 in 20,000 people, over his 42-year career.

When Ockler mentioned that her nephews were sick a lot too with similar symptoms, Hill, who is a professor of pathology, pediatrics, and medicine, wondered about a genetic cause. Only about 10 percent of CVID cases have been identifi ed as having a genetic cause; Ockler didn’t have any of them.

Could There Be a New Genetic Marker Linked to CVID?

Collaborating with a number of Utah colleagues, including ARUP molecular pathologists Attila Kumánovics, MD, and Karl Voelkerding, MD, they delved into research, securing grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Utah Genome Project. They were able to test 30 of Ockler’s family members.

In the Labs: CVID Testing

“Our work here is to help diagnose patients, and genetic testing is one way to do that; once we know the cause of the disease, we can test more specifically, honing in on a specific gene, as is the case with common variable immune deficiency (CVID),” explains Attila Kumánovics, MD, assistant medical director of Immunology and co-director of Immunogenetics at ARUP. He adds that this is much quicker than testing to eliminate possibilities and means results get back to the patient faster. Genetic test results can also open the door for genetic counseling so families can better understand the condition and take steps to recognize and address their family’s health, which might entail preventative steps or earlier interventions.

Infections are very much a part of life, but how many infections are too many before you suspect something else is at play? Unlike many other genetic diseases, there are no outward signs or symptoms that tip you off that genetics is at play here. That’s why it usually takes many years to diagnose these patients.

Attila Kumánovics, MD, ARUP Assistant Medical Director, Immunology; Co-Director,

Currently, ARUP Laboratories tests for 35 genes related to CVID by using sequencing. These 35 genes include more than those that are usually associated with CVID, so the test panel is called Primary Antibody Deficiency Panel. ”The reason is that many of these diseases and diagnoses are hard to differentiate in practice,” explains Kumánovics. His team is working on developing testing for the gene encoding for IKAROS, a protein well known for its central role in immune cell development (see accompanying story).

Many ARUP labs are involved in the diagnosis of CVID involving non-genetic tests—for example, the serum immunoglobulin measurement tests in the Protein Immunology lab, the lymphocyte subset panels in Immunological Flow lab, and the vaccine response tests (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae antibodies, IgG) in the Autoimmune Immunology lab.

ARUP is one of 11 labs in the country offering exome sequencing and will soon be offering genome sequencing. Exome sequencing looks at only the parts of the genetic information that encodes for proteins, while genome sequencing looks at all of the gene’s DNA. Genomic sequencing holds huge promise for the estimated 30 million Americans living with an orphan disease, 80 percent of which are inherited. CVID is one such disease.

They found that many of Ockler’s relatives were missing one of two copies of a gene that codes for IKAROS—a protein well known for its central role in immune cell development.

Meanwhile, 2,000 miles away, Mary Ellen Conley, MD, from The Rockefeller University, independently came to the same conclusion with her own patients. She connected with the Utah team and coordinated what would become an international effort revealing a total of six unrelated families who share similar sets of symptoms and changes in the same gene, implicating IKAROS as the culprit behind their shared disorder. “Often research tries to answer a question that is brought up by the patients,” says Conley.

While some families had a change in just one DNA letter within the gene, others were missing a large piece, or all of it. Each of the mutations cripple a region required for IKAROS to function, a result confirmed by biochemical analysis, suggesting it cannot carry out its critical role in regulating immune B cell development. Indeed, as the experiments predicted, all six families have low B cell counts. In other words, their immune system is misconstructed, likely explaining why they also have low levels of infection-fighting antibodies (immunoglobulins), which are produced by B cells.

Yet one of the most surprising findings, says Kumánovics, assistant professor of pathology at the University of Utah, is that while some who carry the IKAROS mutations are prone to sickness, others appear to be healthy. He adds that understanding the biology that leads to this unexpected resilience could provide clues to overcoming the condition. “These rare patients don’t know how valuable they are. They are providing insights into how the immune system works,” adds Kumánovics.

The findings were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine last March; the Ocklers were the largest family included in the research. This finding makes it possible for doctors to make a definitive genetic diagnosis for this class of CVID, opening a door to precision medicine tailored to patients with the disorder.

We knew that if we could find the cause of her and her extended family’s disorder that we would have the chance to keep others from going through what she had.

Harry Hill, MD, ARUP Medical Director, Cellular and Innate Immunology

In the near future, researchers have what they need to create definitive diagnostic criteria for this new class of CVID. “The diagnosis is rare but that makes it no less difficult for those who have it,” says Voelkerding, professor of pathology at the University of Utah and medical director of Genomics and Bioinformatics, at ARUP. “We think this discovery will help patients around the world,” he adds. “There is no good treatment if you don’t have a good diagnosis.”

Research collaborators also included Sarah South, PhD, Nancy Augustine, and Thomas Martins, MS, from the University of Utah School of Medicine and the ARUP Institute for Clinical and Experimental Pathology® at ARUP Laboratories, and 26 other scientists from institutions across the U.S. and Europe.

What Is Her Hope?

At 71, Roma Jean Ockler continues giving herself weekly gamma globulin shots, which help boost her immune system with disease-fighting antibodies. The mystery of all those infections fought throughout her life is now solved. Looking back, she wonders if her mother or father carried the genetic mutation; she suspects aunts and uncles may have had it—the ones who were sick a lot.

Mostly, Ockler focuses on now. She’s relieved that there are some answers, thus allowing for earlier intervention for her son and grandchildren who must contend with CVID. And her hope? “One day, and I know it will take a lot more research, I hope they treat the disorder so well that it is like a cure.”

HOME

HOME