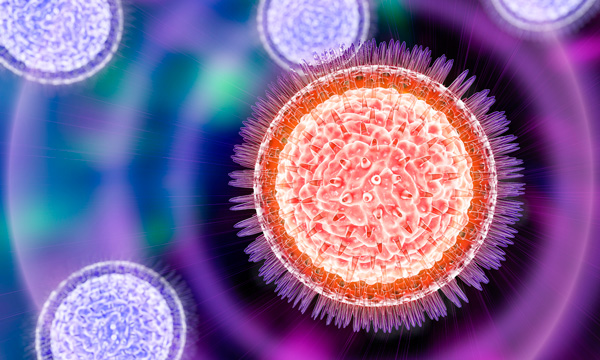

An unusually high level of infection in a Zika-related death could explain unconventional transmission to a second patient.

The first Zika virus-related death in the continental U.S. occurred in June of this year, but even now, months later, two aspects of this case continue to puzzle health experts. First, why did this patient die? It is quite rare for a Zika infection to cause severe illness in adults, much less death. Second, how did another individual, who visited the first while in the hospital, become ill from Zika? This second patient did not do anything that was known at the time to put people at risk for contracting the virus.

Researchers at ARUP Laboratories and the University of Utah School of Medicine in Salt Lake City begin to unravel the mystery in The New England Journal of Medicine. Details from the two cases point to an unusually high concentration of virus in the first patient’s blood as being responsible for his death. The phenomenon may also explain how the second patient may have contracted the virus through casual contact with the primary patient, the first such documented case.

Patient 1 was initially identified as being potentially infected with Zika virus during validation of a real- time PCR test for Zika virus that is currently under development at ARUP Laboratories, and was subsequently confirmed as positive by both the Utah Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“From a clinical perspective, an important finding was that the virus can be transmitted person-to-person by routes other than mosquito bites or through sexual contact,” says co-author Kimberly Hanson, MD, MHS, a medical director at ARUP. “This was the first recognized case, and a very rare one, of a secondary Zika virus infection acquired by contact with a sick person.”

This case emphasizes the need to further understand how Zika spreads and what precautions may need to be taken to prevent spreading. “We may never see another case like this one,” says corresponding author Sankar Swaminathan, MD, chief of Infectious Disease and professor of internal medicine at the University of Utah (U of U) School of Medicine. “But one thing this case shows us is that we still have a lot to learn about Zika.”

“From a clinical perspective, an important finding was that the virus can be transmitted person-to-person by routes other than mosquito bites or through sexual contact. This was the first recognized case, and a very rare one, of a secondary Zika virus infection acquired by contact with a sick person.”

Kimberly Hanson, MD, MHS

Medical Director

The narrative unfolds in the NEJM case study. Last May, Patient 1(a 73-year-old man) traveled to southwest Mexico, a Zika-infected area. Eight days after returning, he started having abdominal pain and fever, and by the time he was admitted to the University of Utah hospital he also had inflamed, watery eyes, low blood pressure, and a rapid heart rate. Despite the medical staff’s best efforts to stabilize him, his condition declined rapidly. During this time, Patient 2 came to visit and reported wiping away Patient 1’s tears and helping to reposition him in the hospital bed. It wasn’t long before Patient 1 slipped into septic shock, and his kidneys, lungs, and other organs started to shut down. He died shortly thereafter.

Even though it’s well known that Zika can cause severe brain damage in unborn babies, symptoms are typically mild in adults. Only nine other Zika-related deaths have been reported worldwide, says Swaminathan. Despite the odds, tests performed after Patient 1’s death revealed that he had Zika.

Further research using Taxonomer, a tool developed by scientists at University of Utah and ARUP Laboratories that rapidly analyzes all genetic material from infectious agents in a patient’s sample, suggested that there were no other obvious infections in the blood that explained his illness. “There was a question of whether this may be a more pathogenic strain. The viral genome sequence didn’t support this, which put more weight on the high viral load,” explains ARUP Medical Director Robert Schlaberg, MD, MPH. Taxonomer also found that the Zika virus that infected the patient was 99.8 percent identical to that carried by a mosquito collected from southwest Mexico, the same region that Patient 1 had visited a few weeks prior.

Seven days after Patient 1’s death, Patient 2 developed red, watery eyes, a common Zika symptom. Tests suggested that Patient 2 had also developed a Zika infection, but in contrast to Patient 1, this patient only had mild symptoms that resolved within the following week.

Like Patient 1’s death, Patient 2’s diagnosis was unexpected. The species of mosquito that carries Zika had not been found in Utah and Patient 2 had not traveled to a Zika-infected area. A reconstruction of events ruled out other known means of catching the virus. An unprecedented transmission by casual contact between the two patients was found to be the most likely explanation.

“This and any future cases will force the medical community to critically re-evaluate established triage processes for determining which patients receive Zika testing and which do not,” says Marc Couturier, PhD, of ARUP.

The authors believe that the reason behind the unusual nature of the case lies in yet another anomaly. Patient 1’s blood had a very high concentration of virus, at 200 million particles per milliliter. “I couldn’t believe it,” says Swaminathan.

“This and any future cases will force the medical community to critically re-evaluate established triage processes for determining which patients receive Zika testing and which do not.”

Marc Couturier, PhD

Medical Director, ARUP

“The viral load was 100,000 times higher than what had been reported in other Zika cases, and was an unusually high amount for any infection.” The observation opens up the possibility that the extraordinary amount of virus overwhelmed the patient’s system, and made him extremely infectious.

Still, what led to the unusually severe infection in the first place remains unknown. Was there something about Patient 1’s biology or health history that made him particularly susceptible? There were small differences in the virus’ genetic material compared to other samples of Zika virus; did they cause the virus to be exceptionally aggressive?

The NEJM case study’s authors include: Marc Couturier, PhD, Robert Schlaberg, MD, MPH, and Kimberly Hanson, MD, MHS, all medical directors from ARUP Laboratories and faculty at the University of Utah Department of Pathology; as well as Sankar Swaminathan, MD, chief of Infectious Disease and professor of internal medicine at the University of Utah School of Medicine and Julia Lewis, DO, from the University of Utah School of Medicine.

Swaminathan says, “This type of information could help us improve treatments for Zika as the virus continues to spread across the world and within our country.”

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and published as “Fatal Virus Infection with Secondary Nonsexual Transmission” in the New England Journal of Medicine on Sept. 28.