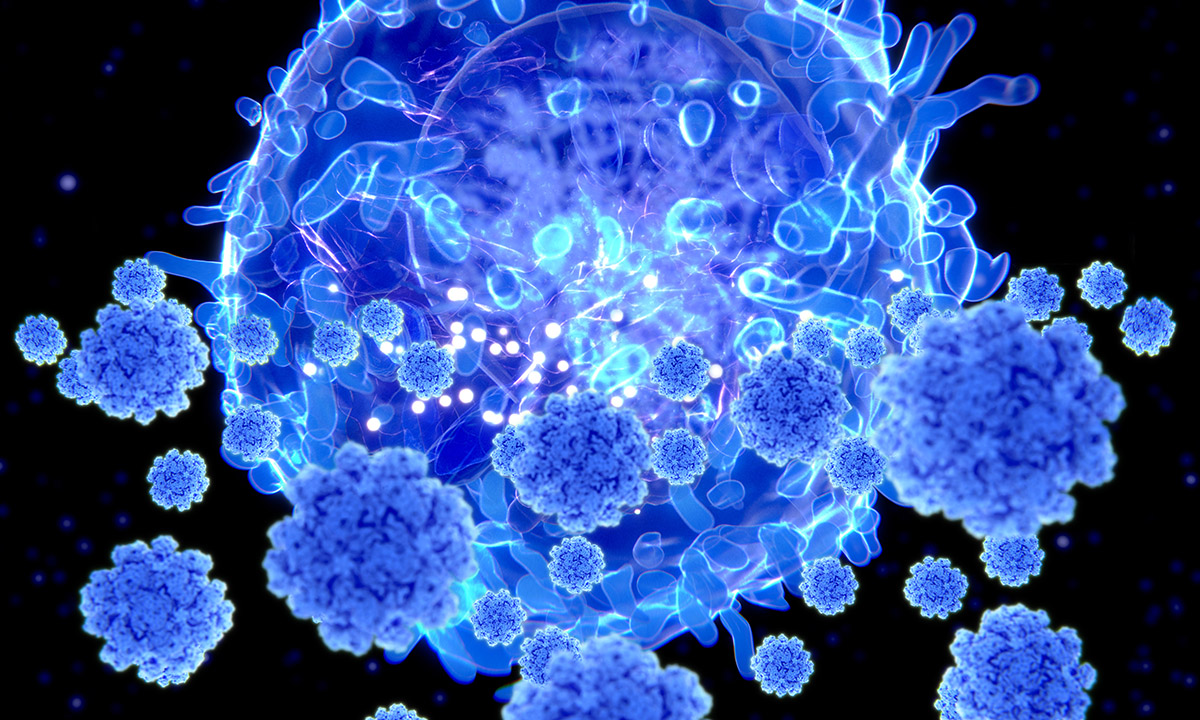

This illustration shows a T lymphocyte cell, or T cell, targeting SARS-CoV-2. When confronted with a new pathogen such as SARS-CoV-2, our immune systems, in addition to developing antibodies, begin over time to call on T cells, a type of white blood cell, not to stop a virus from entering cells as antibodies do, but to prevent the dissemination or propagation of the disease.

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, at a point when the highly contagious Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 has infected millions in the United States alone, most of us have some immunity against the potentially deadly virus. Whether vaccinated and boosted or armed with antibodies produced by natural infection—or both—our population is certainly more protected than it was when community spread of SARS-CoV-2 was first detected in the U.S. in February 2020.

But how and when will we know if we as individuals have built up lasting immunity to COVID-19? What will it take for our communities to reach the longed-for state of “herd immunity,” wherein COVID-19 remains ever present but becomes more manageable, like influenza or the common cold?

Researchers at ARUP Laboratories are among those who have been asking these questions since the start of the pandemic, and they have learned a lot so far, said Julio Delgado, MD, MS, ARUP executive vice president and chief of the University of Utah’s Division of Clinical Pathology. An immunologist, Delgado is the principal investigator in a clinical study launched shortly after ARUP introduced its first SARS-CoV-2 antibody test in April 2020 that is examining correlates of long-term immunity to the virus.

Delgado and his colleagues so far have relied on antibody testing on different specimen types to measure antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 over time in three cohorts (the never vaccinated who have had COVID-19, the vaccinated who have had booster doses but have never had COVID-19, and the vaccinated who have had breakthrough infections). Like researchers elsewhere, they generally have observed that antibodies, whether acquired through vaccination or through natural infection, are protective against SARS-CoV-2 infection for four to six months.

Antibodies—proteins that attach to the virus and prevent it from entering cells to trigger infection—have been the focus of most discussions about immunity to COVID-19 to date. They are critical to the immune response, but they do not paint the whole picture of our complex and adaptive immune systems, Delgado said.

Antibodies are most protective shortly after vaccination or natural infection, but their power wanes over time. They also become less effective as the virus they recognize mutates, he said. This helps explain why Omicron has caused so many breakthrough infections in those who are vaccinated against the virus: The variant is studded with multiple spike protein mutations. Antibodies built up to combat the ancestral strain of SARS-CoV-2 and later variants do not recognize the virus due to the mutations and may not attach to it in order to prevent Omicron from triggering infection.

Because antibody response is something of a moving target, and because antibody tests vary widely, researchers are unlikely to zero in on a generally accepted level of antibody response that signals protection against SARS-CoV-2 and future strains of the virus, Delgado said.

More promising as a possible indicator of immunity, but not as well understood in relation to SARS-CoV-2, is another, longer-lasting way our immune systems adapt to fight off disease.

When confronted with a new pathogen, our immune systems, in addition to developing antibodies, begin over time to call on T lymphocyte cells (T cells), a type of white blood cell, not to stop a virus from entering cells as antibodies do, but to prevent the dissemination or propagation of the disease. T cells essentially kill infected cells, decreasing the severity of the disease. Importantly, researchers are confirming that T-cell responses kick in regardless of how SARS-CoV-2 mutates. T-cell responses also do not diminish over time.

“This is what we’re seeing today with Omicron,” he said. “Even though there are so many infections, fewer people are becoming seriously ill because—particularly for those who have received two doses of a vaccine and a booster dose—they have developed antibodies and also are benefitting from T-cell responses.”

Delgado believes further study of T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 may hold the key to understanding long-term immunity to COVID-19. “In my mind, it may put an end to the question of whether we need to get boosted every six months,” as new strains evade antibodies and antibody levels wane.

T-cell responses are more difficult to study than antibody responses because researchers must experiment using live cells. They must isolate cells from freshly collected blood of previously infected individuals, culture the cells with peptides of the virus, measure T-cell responses, and then correlate the responses with outcomes. Delgado said he, along with Leo Lin, MD, PhD, who is another ARUP immunologist, and Hemant Joshi, PhD, a clinical immunology fellow, are designing a study that would seek to determine whether a certain level of T-cell response signals sufficient protection against serious illness from SARS-CoV-2 without repeated vaccine boosters.

“Ideally, this would result in a test [for T-cell responses] that provides information to determine whether we need to keep getting vaccine boosters, because I don’t believe that’s the solution,” he said.

It also could tell us whether a majority of the population has developed immunity sufficient to signal the end of the pandemic as COVID-19 becomes a disease that is more manageable and results in fewer deaths.

When we will reach this stage remains anyone’s guess, but Delgado emphasized that there is one thing all of us can do to move us closer to the end of the pandemic: Get vaccinated if you’re not already, even if you’ve had COVID-19.

“I cringe when I hear people say, ‘Well, if the vaccine isn’t keeping me from getting infected, what’s the point?’” he said. “The point is that the vaccine doesn’t only produce antibodies, it produces T-cell responses that don’t go away and help prevent severe illness.”

“Imagine the situation we would be in now with Omicron if we hadn’t had the vaccine,” he said. “There would be many more people dying. It would be really catastrophic.”

Lisa Carricaburu, lisa.carricaburu@aruplab.com