One Got It, One Didn’t: A Newborn Test Determines Different Trajectories in the Lives of 2 Siblings

NOTE: This story was originally published in the 2017 Spring Edition of Magnify

“She smiled a lot, crawled at a year, walked at 18 months—this was slow but not alarming. It wasn’t enough to make a pediatrician seek out testing,” said Heidi Wallis about her oldest child, Samantha (affectionately known as Sam). At 2 years old, she “had no words.” Heidi recalled, “I kept saying to myself, ‘She is going to be fine. She is just moving at her own pace.’ Everyone else said not to worry, that I was just being a nervous first-time mom.”

But things didn’t get better. Sam became increasingly more delayed. Wallis spent the first five years of her daughter’s life desperately trying to figure out why Sam was struggling and what would help.

She had been tested for autism at 3 years old, yet she barely registered on the autism spectrum. Despite the long stretches of working daily with Sam at home on behavioral and cognitive exercises—hours of prompting communication through picture cards—and attending ongoing speech and occupational therapy appointments, progress was slow.

It was the seizures that ultimately led the Wallis family to a test that revealed some answers. For several months, Heidi had noticed Sam’s eyes occasionally rolling back. After she videotaped it for their pediatrician to see, the family was referred to a neurologist at Primary Children’s Hospital.

Suspecting seizures, the neurologist ordered a series of tests, including a magnetic resonance spectroscopy that measures biochemical changes in the brain. It showed Sam’s brain had a lack of creatine—an essential nutrient created in the body that provides energy to all our cells.

When she’s spiraling out of control, the best way for me to bring Sam back down to earth is with a hug. It is literally her reset button."

Heidi Wallis

DNA tests confirmed that Sam had a mutation in her GAMT gene, which makes the enzyme guanidinoacetate methyltransferase, or GAMT, that creates creatine. It was a broken process. The GAMT deficiency disorder was only discovered in 1994, nine years before Sam’s arrival on a hot July morning. The disorder is rare; at the moment, Sam is only one of about 110 people worldwide diagnosed with GAMT deficiency.

Additional DNA tests confirmed that Heidi and her husband, Trey, were both carriers. “The mutation from my husband was novel; my mutation they had seen before,” said Heidi. To manifest the deficiency, a child must inherit a mutation from each parent. Some mutations have not yet been identified and will only be discovered with continued research.

What If Sam’s Treatment Had Begun at Birth Instead?

When Sam’s tests came back showing no creatine, her care team turned to Nicola Longo, MD, PhD, a soft-spoken, Italian-born physician well known for his research and expertise in caring for patients with GAMT deficiency. At his University of Utah-based clinic, he guides the care of six patients in Utah and a dozen nationally.

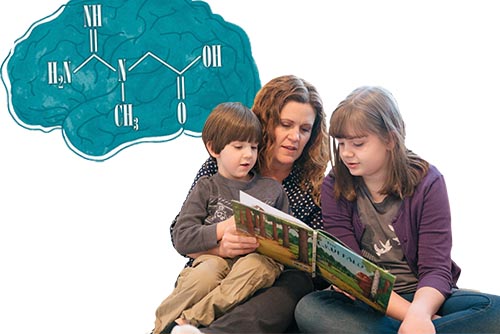

While the effects of a creatine metabolism disorder are severe, the “cure” is relatively simple and inexpensive: a mix of several supplements. Longo fine-tuned the treatment by monitoring his patients’ progress over the years. In addition to replacing the missing creatine, he added ornithine and benzoate to prevent the buildup of toxins in the brain that cause seizures. “We measured and monitored everything biochemically and adjusted it until we saw clinically it was making a difference,” he said.

Longo suspects there are many more children recognized as having developmental delay, cerebral palsy, or seizure disorders who may actually have a creatine deficiency.

“Because the symptoms are so nonspecific, it means there’s a lot of room for misdiagnosis. It may not be as rare as we think,” said Longo, who is chief of the Division of Medical Genetics and co-director of the Biochemical Genetics and Newborn Screening laboratories at ARUP. When these supplements are taken, families see dramatic changes. “I’ll get a call 24 hours later saying a child seems completely different,” said Longo. He added that some children start walking within a month of starting therapy.

We measured and monitored everything biochemically and adjusted it until we saw clinically it was making a difference."

Nicola Longo, MD, PhD, Chief, Division of Medical Genetics; Co-Director, Biochemical Genetics and Newborn Screening Laboratories, ARUP Laboratories

Almost immediately, Sam’s speech improved. “Ba, ma, da” became “ball, mommy, duck.” Within nine months, Sam was stringing together five or six words at a time, excitedly sharing what she wanted to eat, where she wanted to go. “She was so excited to finally be heard and understood,” said Wallis.

What if Sam’s treatment had started when she was a newborn instead of a 5-year-old? She would likely be navigating middle school like any other 13-year-old girl. Wallis knows, because her son Louis, born eight years after Sam, was tested for the disorder as a newborn. When he tested positive, he began receiving the supplements immediately.

Today, Louis is a rambunctious preschooler with no signs of slowing down. “I’ll never stop watching him super close, looking for any hints or signs of delays,” confided Wallis. “He’s going to grow up like other kids, whereas Sam will need me for the rest of her life.”

For children with a creatine deficiency, there are no specific outward symptoms at birth; developmental delays between 6 and 12 months of age are the first signs that something is awry. Catching the disorder at 5 years old, the age at which Sam was diagnosed, cannot turn back the clock. The developmental damage will have already been done.

What If Every Child Could Be Tested as a Newborn?

One day in 2008, Longo went home and shared with his wife that he had seen his first patient with GAMT deficiency in clinic and felt there was something more that could be done to prevent this from happening to other families.

The conversation may have ended there, but the topic hit close to home, or actually, work. His wife, Marzia Pasquali, PhD, a professor in the Department of Pathology at the University of Utah, was instrumental in developing the newborn testing program in Utah and is the head of the Biochemical Genetics and Newborn Screening section at ARUP Laboratories. She, too, felt there was more they could do.

“We saw how we could include this into our other newborn screening test analysis with minimal changes,” recalled Pasquali. Such screening was already being done in a Canadian province and in Australia. She began developing a test that could accurately diagnose GAMT deficiency.

We’ve always tried to do the best we can for families, but now we’re taking it to a different level. We have the chance to give these kids a normal life. It’s a terrible waste to do nothing."

Marzia Pasquali, PhD, Medical Director, Biochemical and Newborn Screening, ARUP Laboratories

She tested 10,000 archived blood spots and was able to identify the three known GAMT deficiency samples mixed in. In 2015, the test was added to the newborn screening panel for the state of Utah—the first and only state to offer it so far. With more than 50,000 births a year in Utah, it is just a matter of time before a child is identified with a creatine deficiency. Pasquali is now working on the implementation of this screening nationally.

“With this screening, as time passes, we may learn more about the frequency of this disorder,” said Pasquali, who estimates that one in 120,000 children will test positive for it. Based on current U.S. birth rates, that is about 33 babies a year.

Right Now, Diagnosis Is 100% Luck

Witnessing the dramatic developmental differences between Sam and Louis further motivated Longo and Pasquali to push for screening nationally, with the Wallises leading the charge. They’ve become a cadre of advocates; Longo serves on the medical advisory board of the Association for Creatine Deficiencies, of which Wallis is the administrative director and a board member. They all travel to meetings in Washington, D.C., to join with families to lobby for screening.

“We’ve always tried to do the best we can for families, but now we’re taking it to a different level,” said Pasquali. “We have the chance to give these kids a normal life. It’s a terrible waste to do nothing.”

“Diagnosis for a GAMT kid is 100% luck right now. A full life or a life of misery is currently left to chance,” said Wallis. She accepts that there was no testing available when Sam was born; she cannot accept the fact that there are children being born today whose families will end up on the same diagnostic odyssey she was on, asking repeatedly, “What is wrong with my child?”

“There is a sense of urgency,” stressed Wallis. “It may be a rare condition, but the impact on the individual, their families, and communities is dramatic. And it just doesn’t have to happen.”

A Spoonful of Sugar Does NOT Help This Go Down!

“If your child has been telling you about his/her friend named Sam who ‘doesn’t’ talk’ and you’ve been wondering what that means, we thought we would tell you a little about this week’s Super Star, Sam.”

So began a letter from Heidi Wallis, Sam’s mom, to her daughter’s kindergarten class. Six months earlier, Sam had been diagnosed with GAMT deficiency, providing some long-sought answers and introducing a whole new routine into the Wallis’ lives.

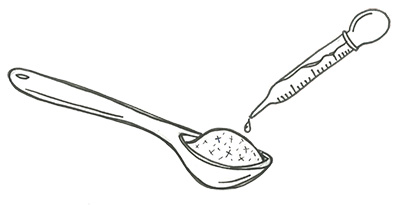

Now 13 years old, Sam has a routine that’s structured around the mix of “nasty tasting” supplements that she must take four times a day to counter her creatine deficiency and deter seizures. Each day starts with a tap on the shoulder at 6:30 a.m. to wake up Sam for breakfast and her first dose of creatine—a full 30 mL syringe.

Each Sunday, Wallis spends an hour and a half preparing 28 syringes for the week ahead—five of these doses, Sam will take at school. “It looks like a drug bust scene in our kitchen,” admitted Wallis with a laugh.

There’s no super-secret ingredient in this mix of supplements (creatine monohydrate, L-ornithine, and sodium benzoate). “You can buy them on Amazon,” quipped Wallis. Body builders are drawn to creatine for its muscle-building properties.

The Taste Challenge

Early on, enticing Sam to swallow the powder was difficult; she was at an age when most kids were pushing away their broccoli. However, refusing wasn’t an option. This powdered mix—or lack of it—was why Sam was developmentally delayed. “It will make you strong and smart,” coaxed Wallis. She experimented by masking the bitter flavor with Kool-Aid, apple juice, apple sauce, and smoothies. “She hated it all, sometimes throwing it up.”

By the time Sam was 8 years old, they had figured it out. “She loves Caffeine-Free Diet Coke, so I would set one in front of her, crack it open, and then say, ‘All right, let’s do this,’” said Wallis, who would use a syringe to squirt the supplements toward the back of Sam’s throat. Then Sam would grab the Diet Coke and start guzzling it down to wash away the flavor.

When Sam’s little brother Louis was born, his creatine deficiency was diagnosed right away. He was swallowing the supplements as a newborn, which desensitized him to the taste and prevented the disorder from taking root. “Although he still grimaces every time,” said Wallis.

Wallis keeps Sam and Louis’ diets low in arginine (an amino acid), so it’s a low protein diet. Arginine can lead to the buildup of a neurotoxin that leads to seizures, and both Sam and Louis are missing a key enzyme that prevents this buildup.

To help stop seizures, Sam has been taking cannabis oil. “She is a sweetheart when she is feeling like herself. But for days leading up to a seizure she can be like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” confided Wallis. A seizure leaves Sam feeling exhausted and frustrated for the rest of the day.

“When she’s spiraling out of control, the best way for me to bring Sam back down to earth is with a hug,” said Wallis. “It is literally her reset button.”